Let me confirm that there are over 600 elephants in the main section of the Addo Elephant Park (AEP) and they seem to be doing rather well. They are eating, drinking, procreating, swimming and enjoying each other’s company as never before. My wife and I have been to the park every few weeks in recent years and we usually see more than 200 elephants on each visit. It is always an exciting experience to observe such a thriving population. Often, individuals are almost within in touching distance, although I would never actually touch one.

As the elephant population of Addo continues to grow and the park management does not appear to have any plans to reduce the numbers, it once again raises the question of ‘How many elephants can the Park carry?’. Is there a limit, or should the authorities simply allow numbers to grow organically? Is there some kind of birth control that could be applied; or is culling the only answer?

This is not a new debate and not one localised to Addo. It sometimes appears that there are just too many elephants at AEP particularly when game viewing at the Hapoor Waterhole. The veld around the small dam is trampled flat by the hundreds of elephants that come to drink and play in the mud every day, especially during the summer months.

Carrying capacity of elephants is intensely debated with reference to the Kruger National Park (KNP). It covers a vast area of more than two million hectares, so how many elephants can Kruger carry? Ron Thomson1 wrote in his book, ‘A Game Warden’s Report’ that by the early 1960s the elephant population of that park first exceeded 6,000. It reached 7,000 by 1967 and management decided that the population was at an ideal level and that it was time to begin culling.

The argument for culling centres around how much depredation the local ecosystem can sustain. Elephants need to eat a lot and so they have a significant impact on the environment. Historically, culling was not necessary because humans had not yet erected fences all over the countryside so herbivores could always move from one place to another where the grass (and foliage) was always greener.

Thomson wrote that, “Excessive herbivore populations, for example - perforce over-utilise their habitats causing the habitats to change in character. And if the responsible population is not reduced in number, by management, sensitive plant species soon become locally extinct”.

This view held sway until 1994 when the KNP population was still around 7,000 elephants. Since then, small numbers have been moved to other parks, including Addo, but the translocations have had little impact on the overall population growth. According to Thomson, the elephant population of the Kruger elephant habitat had grown to 11,500 by 2004.

Helicopter counts during 2008 estimated that the Kruger elephant population had grown to 12,930. On World Elephant Day, 12 August 2024, the South African National Parks (SANParks) declared that there are currently about 30,000 elephants in the KNP2.

These figures are official estimates, but they may not be all that accurate. Game counting, even for animals as large as elephants combines helicopter rides with educated guesses. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the elephant population of the KNP has increased immensely over the last three decades.

This huge growth has once again caused people to believe that there are too many elephants in the park. Ross Harvey3 wrote an opinion piece in the Business Day newspaper, “If you’ve had a conversation with anyone recently returned from the Kruger National Park (KNP), you’re likely to hear: ‘It was lekker, but there are too many elephants. The damage to the trees is crazy’.”

He wrote that this type of comment is used to justify the myth that the culling of elephants is a ‘necessary evil’. Harvey argues that the concept of a fixed carrying capacity is obsolete and blames the “historical thinking in conservation that idealises wild landscapes as static entities that must possess a certain unchanging proportion of beautiful old trees to other plants and animals”.

The argument against culling roughly posits that the population of elephants will continue to grow organically until it reaches something closer to a dynamic ‘carrying capacity’, even if that term is out of favour.

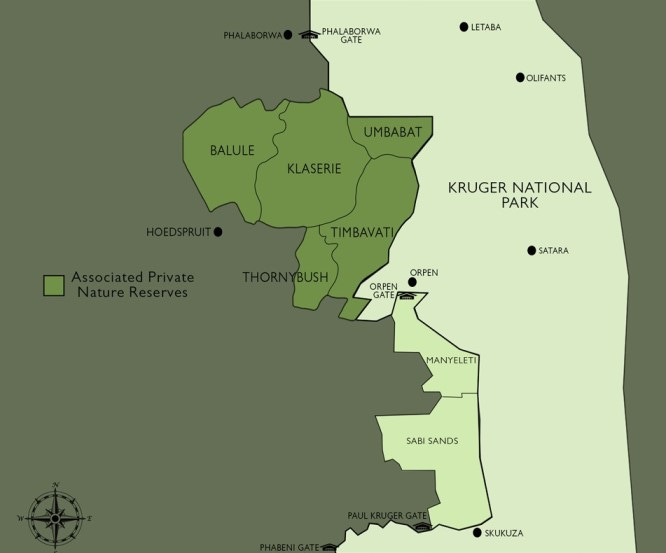

The Associated Private Nature Reserves4 bordering along the western side of the KNP carry part of the blame for the burgeoning elephant population of the Greater Kruger. There are no fences between the KNP and the private reserves so wildlife are free to move wherever they please. The problem is that the private reserves want to guarantee great elephant sightings to their well-heeled guests on their own piece of land, so they have built a dense array of artificial water points to attract elephants and other wildlife. Harvey wrote that elephant population in the private reserves almost doubled from 1,666 in 2012 to 3,144 in 2021.

In an effort to manage the spatial distribution of elephants, the KNP management has closed about two thirds of its artificial water points.

SANParks has not made public any specific details on how it plans to accommodate the growing elephant populations in Kruger and Addo. However, the Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment reviewed its National Biodiversity Economy Strategy5 (NBES) last year suggesting that licences to increase trophy hunting would provide revenue of R27.6 billion (R19 = One U$ dollar) by 2036. This is an increase from R4.6 billion in 2020. These figures are not substantiated with any data.

The strategy is packed tight with government-speak gobbledygook. This is Goal 2 of the NBES:

Consumptive use of Game from extensive wildlife systems at scale that drives transformation and expanded sustainable conservation compatible land-use

It basically means that they want to allow more hunting.

The same section has bizarre statements such as:

. . . there is potential for additional hunting of leopard in a manner that promotes the thriving of the leopard species in the wild with pointed reduction of poaching.

How hunting leopards is good for them can only be understood by government officials who don’t know the difference between a leopard and a crocodile.

The NBES is a nightmare and we still don’t know what is going to happen with the burgeoning elephant populations in Addo and Kruger.

I sincerely hope that every country in the world bans trophy hunting.

Further Reading:

Elephant Management Plan, Kruger National Park, 2013-2022. Mr Danie Pienaar, Head of Scientific Services, SANParks, Skukuza

Addo Elephant National Park, Park Management Plan for the period 2015 - 2025, SANParks

Kruger threatens to re-erect game fences over private reserves’ poor governance - Louzel Lombard Steyn in Conservation Action Trust

Elephant Population Numbers in Kruger – A Game Warden’s Report, by Ron Thomson. An excerpt on the Siyabona Africa website.

South Africa’s Elephant Management is an exemplary success story. SANParks 12 August 2024.

The myth of ‘too many elephants’ by Ross Harvey in Business Day. 2 July 2024

Reviewed National Biodiversity Economy Strategy Government Gazette - 8 March 2024

Excellent piece, very thought-provoking. I’m not sure to what extent it’s possible to judge when a protected area has truly reached carrying capacity. It would obviously be tragic if it got to the point that elephants had to be culled. Of course, if we had preserved the landscape connectivity and not put up fences, we wouldn’t even need to have this conversation.

Thank-you for your words of encouragement. You are of course absolutely correct about the problems we humans created with our fences. I believe that several private parks in the Eastern Cape are negotiating plans to drop mutual boundary fences. This will create larger open spaces and hopefully create ecosystems closer to what they originally were.

If you have suggestions for future newsletters, please don't hesitate to send them along.

Best wishes,

Steven